Submitted by Ralph Larsen

October, 2001

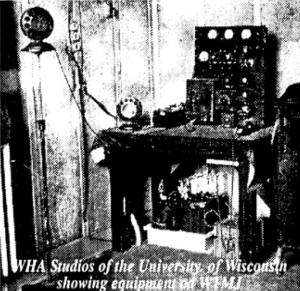

During the early part of it’s history, the Milwaukee Journal was a pioneer in many aspects of radio and TV broadcasting. The company conducted many experiments at its own expense with permission of the FCC and its predecessor, the Federal Radio Commission.

The Milwaukee Journal experimented with fax transmission, remote broadcasting, high fidelity broadcasting, FM and television transmission: both spinning disk and electric transmission back in the thirties.

It did not start out so promising. Soon after getting its AM broadcasting license in 1927, the Journal was complaining to the Federal Radio Commission about sharing its frequency with other stations in Florida and Maine. When they didn’t get satisfaction from the Federal Radio Commission, it took the other stations to court. WTMJ became known as “the most litigated station in the century” according to an article in Broadcasting.

In its first years, it is apparent that the Journal wanted WTMJ to be an all clear radio station. That goal was never realized.

There were several factors that allowed the Journal to experiment. WTMJ dominated the local radio scene. According to the national and local surveys in Milwaukee, WTMJ was listened to by far more people than all the other radio stations combined. The Milwaukee Journal had an extensive survey system started in 1933 which they felt was superior to any national survey system. The Journal not only surveyed broadcasting, but also conducted surveys on who bought radios and how many and what brand were sold in Milwaukee. Not only did WTMJ benefit from the Milwaukee Journal’s deep pockets, the station was managed by Walter Jay Damm, who felt that radio and later TV were the natural heritage of the press. In 1936, Walter Damm said: “I have always felt that the logical operators of radio stations, by reason of their long experience in serving the public, are newspaper operators. As I have so often expressed myself, radio can take its lesson in practically every department of its operation from the newspaper, from business practices to program continuity.” Walter Damm was the president of the National Association of Broadcasters for several years.

The early experiments with fax transmissions were due to the newspaper’s interest in using this medium for transmitting pictures to the newspaper. These experiments started in 1929 with very small still pictures. These experiments only lasted a few years, but did resume in 1934. In that year they successfully transmitted a crude picture at only 40 lines per inch. They used the frequency of 1614 kHz. In 1966 interviews, Phillip Laeser, who supervised the fax experiments said that both the high and low frequencies were used for fax transmission. They first used the ink method, but then went to chemically treated paper. The ink system used 4″ wide paper and the chemically treated paper 8″ wide. The paper was processed at about 1″ per minute.

High Fidelity broadcasting was also being investigated in the early thirties. AM broadcasting only has a range of 50 to 5,000 Hertz. Many microphones manufactured in the thirties had a far better response. The Journal applied for a high fidelity station here in 1934 on the high end of the AM band, but was turned down. They did apply and were granted an experimental high fidelity AM station at 31.6 MHz, W9XAZ. This was known as APEX radio. There were no commercial radios that operated at that high a frequency and the radios were custom built. Members of the Milwaukee Radio Club (a group of ham operators) had a weekly program and reported on the results. The station was on from noon to 10 p.m. each week. The operating power was 500 watts. The station broadcasted from the top of the Schroeder Hotel. The station’s frequency was later changed to 42 MHz. The station survived for several years. In fact, when the Journal’s original request for an FM station was made to the FCC, they proposed that W9XAZ be increased in power so that high frequency AM and FM could be compared. The FCC denied permission to increase the power of the AM station, but the station continued to broadcast until 1941. During its peak, the station broadcasted ten hours a day. They did original programs and did Marquette basketball games. In an interview done years later, Phillip B. Laeser, the chief engineer for the station, recalls that they received calls from overseas and from the coasts on their broadcasts. But he also states that “nearby areas had more trouble as the signal went over them,” a reference perhaps to the problem of skipping.

Did Milwaukee FM experiments inspire Zenith to build The Major WTMJ applies for a TV license in 1938? In the next issue I will be examining the early history of WTMJ’s experiments with FM and television broadcasting.